Chapter 1: The Diagnosis

I saw a very interesting patient a few weeks ago. He is 83

and really has no medical history other than that he has mild dementia. There

are several interesting aspects to this case. I tweeted a few teasers about it

last week. I will follow up on those tweets here with Chapter 1 of my story. In

the next few days, I will round out the story with some very interesting issues

around medical decision-making.

Chapter 1: The Diagnosis

This gentleman is a robust and active man with poor

short-term memory. If you saw him on the street, you’d think nothing other than

that he is an older guy who looks healthy. He can’t really remember what he had

for breakfast each day, but he is happy and active. He and his wife like to

walk. In January, they were walking around San Francisco. She looked back, and

saw him on the ground. By the time she got there, he was awake and being

attended to by bystanders. She thought he might have tripped (what we call a

mechanical fall). Remember, this is a very active and robust man who has never

fallen. So they took him to a local emergency room. His triage diagnosis was

“mechanical fall”. He was evaluated and found to have had a laceration on his

head. It was stitched. The remainder of his physical examination showed that

his vitals were normal, and his cardiac exam was described as “regular rate and

rhythm”. He had an unremarkable head CAT scan and an unremarkable set of labs.

His electrocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy (thick heart muscle).

He was deemed stable and discharged a few hours later.

A month or so later, the man and his wife were again walking

around San Francisco. This time they were late for a performance and were

rushing up a hill. Again, the wife looked back and saw her husband on the

ground. She again assumed he fell. Again, he went back to the same emergency

room and they “evaluated” him. He was again found to have normal vital signs.

This time, the doctor examining him described a 2-3/6 systolic murmur. The ECG

again showed left ventricular hypertrophy. His labs were normal. He was again

diagnosed with “mechanical fall” and sent home. However, this time someone

thought it would be good to do a stress test, presumably to rule out coronary

artery disease.

A few days later, the patient showed up at an office and got

on a treadmill for a stress echocardiogram (a stress test). I should note that

stress testing started with just exercise and an ECG. You can learn a lot from

the exercise and when combined with the ECG, you can diagnose coronary artery

disease with modest sensitivity and specificity. With the advent of echo

(ultrasound), it was found that one could improve the sensitivity and

specificity of stress testing by adding echo or other imaging. The protocol is

that they do a quick echo before the test, the patient exercises, and then they

do a repeat echo after the test. If one or more walls of the heart shows signs

of not working well with exercise, the test is considered positive.

In this case, the patient had a quick echo before the

treadmill. This is not a comprehensive echo. Generally patients are also

examined before stress testing. After the resting echo, the patient walked for

a few minutes. Apparently he then passed out cold. It is not clear whether the

second echo was performed before or after the time that he passed out.

Regardless, it was with this second echo that they finally made the diagnosis

of severe aortic stenosis. At this point, the patient was rushed to the

hospital and told that he needed urgent aortic valve replacement (open heart)

surgery. In a subsequent post, I will examine the very interesting medical

decision making involved in this case. For now, I want to discuss a few things

I find interesting about the diagnosis (or lack thereof) of aortic stenosis.

First, some background on aortic stenosis. The heart has

four valves. Two connect the upper chambers (the atria) to the lower chambers

(the ventricles). They are called the AV valves. The right-sided AV valve is

called the tricuspid valve, and the left sided AV valve is the mitral valve.

The other two valves cap the right and left-sided outflow tracts. As it sounds,

this is the conduit that connects the ventricles to their main arteries. On the

right side, the pulmonic valve connects the right ventricle with the pulmonary

artery. On the left side, the aortic valve connects the left ventricle to the

aorta. These are three leaflet valves (normally). Aortic stenosis occurs when

the leaflets of the valve become stiff and don’t open well. This increases the

resistance against which the ventricle pumps and if not fixed, can lead to

heart failure, heart attack, or sudden death.

There are many kinds of aortic stenosis. The most common is

called “senile” aortic stenosis and one does not have to be senile to get it.

In this case, the “senile” refers to old age. We don’t understand the

biological mechanism underlying the development of this condition, but it

involves the deposition of a significant amount of calcium in the valve

leaflets. As with many things in medicine, aortic stenosis is classified as

being mild, moderate, or severe. People can live normal lives with severe

aortic stenosis for many years. Eventually, the high pressures the left

ventricle faces causes it to thicken (hypertrophy), and eventually, this leads

to damage to the muscle and eventually heart failure, heart attack and death.

Before a few years ago, there were only two treatment

options for the treatment of aortic stenosis. One could replace the valve

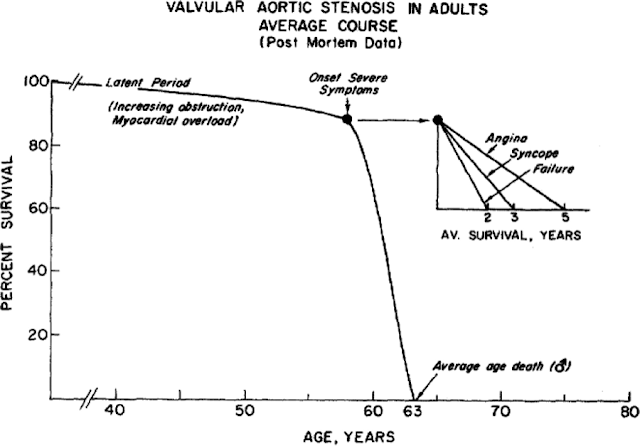

surgically, or one could do nothing at all. As you can see in the figure here,

once a patient experiences symptoms of heart failure, angina (chest pain), or

syncope (passing out), the risk of dying is high. This is a landmark figure

from one of the greats of American Cardiology, Eugene Braunwald. As you can

see, with the onset of these symptoms, patients invariably die within 2-5

years. With syncope, what our patient had, patients live no more than 3 years. With

surgery (or with the other newer options I will discuss later), there is

typically a 5% chance of dying during or after the procedure, but if

successful, patients can go on to live nearly normal lives.

|

|

· JOHN ROSS AND EUGENE

BRAUNWALD Circulation. 1968;38:V-61-V-67

|

So this is a very long way of saying that this is a critical

diagnosis to make. There are few instances in medicine where missing the

diagnosis can have such extreme consequences. Let’s examine what happened

again. A healthy but mildly demented 83 year-old “falls” for the first time

while walking. He falls so hard that he cuts his head and requires stiches.

People who have never fallen don’t often fall and hit their head unless

something is very wrong. He can’t recall what happened and his wife did not see

it. I want to interject here that the typical way one diagnoses aortic stenosis

is with a stethoscope. Old fashioned it may be, but AS (as we call it) has a

very distinct and obvious murmur. Third year medical students could make the

diagnosis with ease. Or at least, they could or should hear a murmur, recognize

it is not normal and then seek more information. On his first visit, either

nobody listened to his heart, or they really had no idea what they were doing.

There were some other clues such as the left ventricular hypertrophy on the

ECG, but mainly this diagnosis is made on history and with a previously healthy

83 year old who has possible syncope (leading to hitting his head)while

walking, aortic stenosis has to be at the top of the list of things to think

about.

But nobody did, and he went on his way. Quite luckily for

him, he had another episode of syncope just a few weeks later. This time, a

doctor did recognize a murmur. Yet this same doctor ignored the previous

history, the current history, the ECGs and his own physical exam. Fortunately

again, this doctor decided, incorrectly, that he should order a stress test to

rule out coronary artery disease.

Our patient shows up for his stress test. Doing stress tests

on patients with significant aortic stenosis can be fatal, so it is considered

a near strict contraindication to do an exercise treadmill test on a patient

with severe AS. Standard practice (at least when I was a fellow) is to examine

each patient with the specific intent of making sure they did not have

significant AS. In this case, again, that either did not happen (likely) or the

cardiology fellow who saw the patient before the procedure cannot use a stethoscope

(maybe). It gets worse. In this case, the patient also had an echo before his

stress test. Here, a trained ultrasound technician would examine the heart to

find the best images for the stress test. While they are not specifically

tasked with doing a complete exam, my experience is that most good echo techs

would note severe AS at this stage and would notify the doctor.

Lucky for this patient, he survived his stress test, but he

very well might not have. I count that there were 5-7 people and an echo tech

who could have and probably should have made the diagnosis before the patient

collapsed on the treadmill. This is a testament to a few things and I do not

think it is entirely incompetence. First, people most definitely do not have

anywhere near the expertise with the physical exam that they used to. It is a

very difficult skill to learn and even harder to teach. Second, this is a great

example of the telephone-effect of medicine. The first “fall” was thought by

the wife to be a fall. She was likely very convinced that it was a fall and

convinced the doctors in the first emergency room visit that it was just a

fall. In the fast-paced world of emergency medicine, it is easy to get attached

to a diagnosis and once one is made, it is extremely difficult to unmake it. I

consistently teach the residents and students to question each and every

diagnosis they get from the emergency department (or the night float resident,

or me or anyone else). I say this not because they should not trust them, but

because a diagnosis is an assumption, and rejecting assumptions is their job.

In this case, the best explanation I can make is that the story was told as a

fall and that story stuck. From that point forward, each and every person who

saw this patient accepted the diagnosis of the first person who had been

convinced by the patient’s wife who had not witnessed the event.

So this story does not end here. Remarkably, there is much

more to it. In the next chapter, things will get technical. But the case

illustrates some of the many challenges physicians, families, and patients face

in making difficult decisions, and I think it is worth sharing. Thank you for

patiently reading through this (if anyone really did).

Comments

Post a Comment